“In India, the emphasis is on marks than practical skills. But it is these practical skills that later help children not just in securing jobs but also in becoming innovators.”

As a 90s kid, one of the biggest milestones in my school life was using a computer for the first time. I may have been in the second standard at the time, and the idea of the internet was fascinating to me. It felt like sheer magic!

But, as I grew older, I realised how privileged I was to be studying in a school that enabled such access. The glaring digital divide in India correlates to one’s financial footing.

For Shoaib Dar, this understanding came when he was working at a government school as a fellow for Teach for India (TFI). The young teacher addressed a simple question to students in class 7–How many of them had ever used a computer?

“There were 30 students in my class. But only one girl raised her hand. I was shocked! That was when I thought that this situation needed to change,” says the 29-year-old.

The big gap

The Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) report of 2018 surveyed 596 government schools in 619 districts in the country. The survey looked at different parameters of education that indicated how well the children learned in schools. It revealed that only 21.3 per cent of schools had computers.

“There was a need to improve digital literacy among kids while making the process interesting. On top of that, the curriculum needed to be drastically changed to accommodate logical thinking and problem-solving,” recalls Shoaib.

But, the problem that lay ahead of him was finding computers that weren’t too expensive. This would mean they could buy more computers, and thereby, reach out to more children.

Shoaib began speaking to his engineer friends who told him about Raspberry Pis. These are low-cost and smaller computers, priced between Rs 4,000-5,000 and readily available.

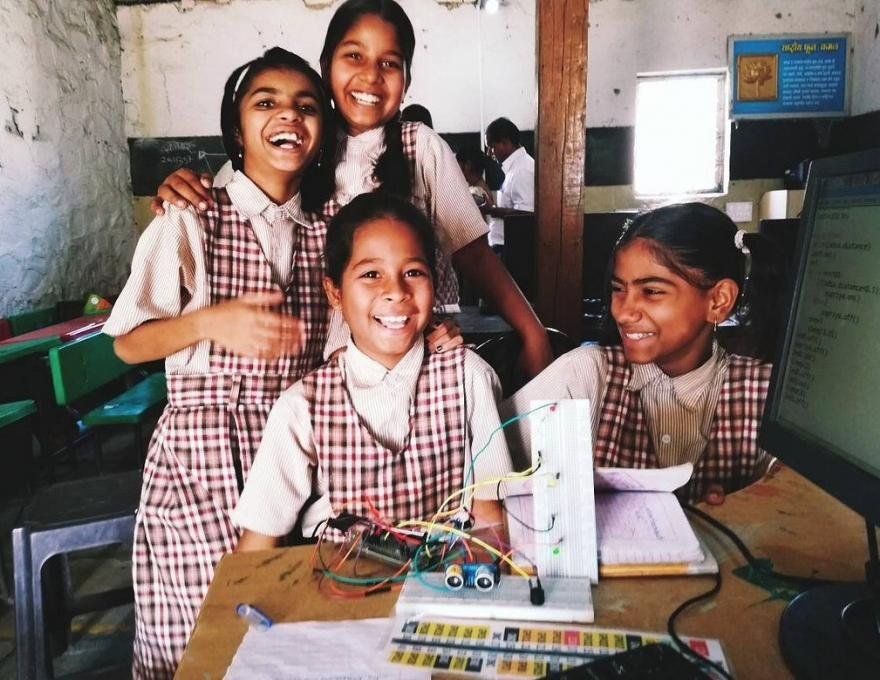

In his second year of fellowship, Shoaib decided to carry out a pilot project at the school he was teaching. He sought help from two of his friends and they set up a 10-day boot camp where they installed four Raspberry Pi computers. They taught Scratch programming to kids to create their own games, animations, and stories.

He saw how this programme was successful as the kids were more enthusiastic; they were also using their computer programming skills to innovate solutions to everyday problems. Thus, in September 2017, he decided to formally found the Pi Jam Foundation, an NGO that would be the right platform to scale their operations.

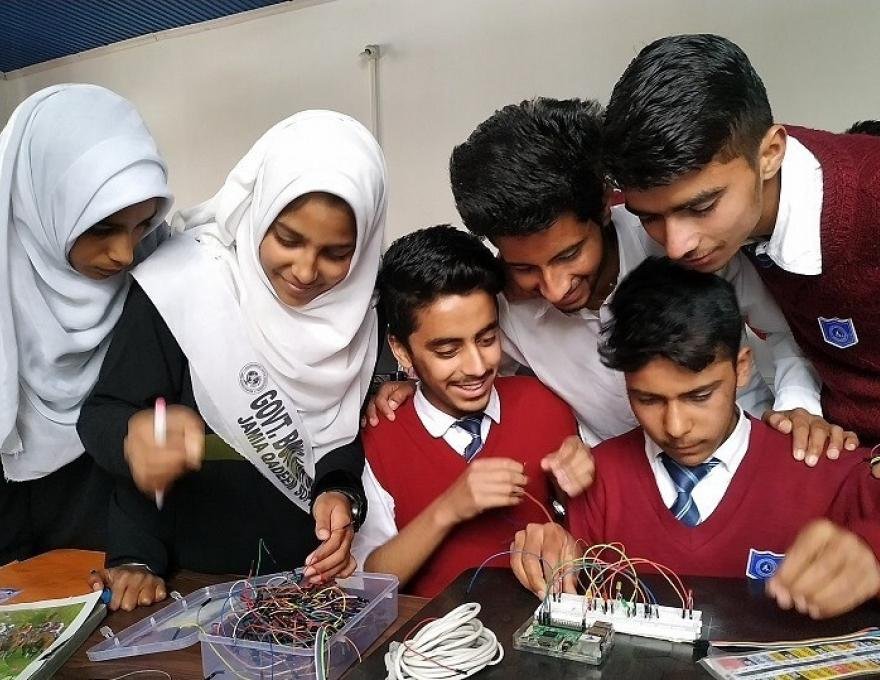

Now, Pi Jam Foundation has reached over 15,500 kids from 51 schools, across Maharashtra, Telangana, and Kashmir. They have installed 400+ computers across these schools for free!

Additionally, the NGO has come up with innovative ways to ensure kids don’t stop learning during the lockdown. They developed ‘Game of Corona’, an interactive game in the form of snakes and ladders, that informs children about the dangers of Coronavirus.

The NGO has also rolled out creative computing sessions so that the kids can access them online on government portals like ‘Diksha’, the national digital infrastructure for teachers. These focus on Game Design and Animation, which is available in Marathi. Now, they plan on making these available in other vernacular languages.

Engineer-turned-Educator

Originally from Srinagar, Shoaib came all the way south to pursue his Mechanical Engineering degree from the Vellore Institute of Technology. After completing the degree in 2013, he decided to go back home and figure out what he wanted to do.

“My father and his group of friends in Srinagar were running a local NGO called, ‘Dawn’. They focused on issues like promoting drug de-addiction programmes, working with local communities, creating awareness on mental health issues, among others. I ended up working there for about eight months,” he says.

He then moved to Bengaluru and started freelancing, designing machine parts, creating 3D models for life jackets etc. At this point, he realised how much he loved working practically than just focusing on subjects in theory.

“As a child, I loved making things rather than just sitting and reading text. Most of my learning has been based on experiments that I did by myself. But, our education system does not provide a child with that space to explore their creative side. I began asking myself how I could contribute to bring about a systematic change,” he says.

Shoaib understood that he would have to work as a teacher. He started researching, and when he saw the TFI fellowship application towards the end of 2014, he applied in a heartbeat.

He was soon selected for the programme and was assigned the Rajashri Shahu Maharaj PMC, a Municipal School in the Mundhwa area in Pune. The fellowship lasted from 2015 to 2017 and he taught Science, Geography, and Math to 60 students of classes 7 and 8.

This was a great period of learning for Shoaib and he started making important notes.

He noticed that the education system was quickly developing in the West with a focus on subjects like mathematics, science, and computers. By skilling their children, they were breeding a cadre of smart innovators who went on to solve the world’s problems.

“This was a stark contrast to the education system and learning patterns in India. Here, the emphasis was on marks than the dissemination of practical skills. But, it is these practical skills that would later help children not only in securing decent jobs but also in becoming innovators,” shares Shoaib.

To beget critical thinking and problem-solving skills, he set up a community space within the school. Since the school didn’t have a science lab, this space served the purpose of an ‘Ideas Centre’.

“This experience brought me closer to the communities, which helped my understanding of their conditions. To get the kids interested, the learning had to be contextual. We started looking at their daily problems and possible solutions,” recalls Shoaib.

These were the events that ultimately led Shoaib to carry out the pilot project, start the Pi Jam Foundation, focus on skill training, improve digital literacy, and develop a curriculum that was interesting for the students.

Nurturing a generation of innovators

Shoaib was certain about one thing– he wanted the kids to enjoy the process of learning.

“Children feel that computers are these complex devices that control them. I want them to understand that it is actually the other way around. Also, I did not want them to feel that working with computers is a hobby or an extracurricular activity. I want them to see the potential of learning these skills and how they can be participants in shaping the changing digital world,” he says.

To carry out these objectives, Shoaib developed a curriculum that would pique the interest of students from classes 5-10. About 50 teachers from these schools have been trained to implement this curriculum in their respective schools.

The first focus area is promoting ‘Problem-solving’. “Before one finds a solution, it is important to identify a problem and understand its different aspects so that a viable solution can be put forth,” he explains.

The second component of this curriculum is ‘Physical Computing’, which is teaching kids how to harness technology to come up with solutions. This is where improving the scale of digital literacy takes place.

Further, training is not just on the basics of operating a computer but, programming, interacting with the physical environment, and working with other devices to come up with a viable solution. Here, Shoaib gives an example.

“The kids started looking at accidents related to two-wheelers and they wanted to come up with a solution. They used a sensor whose interface is connected to the computer. This sensor is attached to a helmet and a motorised latch is placed over the vehicle’s keyhole. Now, only when the rider wears the helmet, the latch opens up, allowing the key to be inserted and the vehicle to start up. This was really innovative,” he explains.

The third component is, ‘Design thinking’ which is very similar to problem-solving. But here, the kids are taught to understand and approach any problem empathetically, while also using reliable data. They try to look at how and why the problem is pertinent, who is most affected by it, and its root cause. “This gives the act of problem-solving a humane aspect. I believe that this skill is going to enable children to tackle complicated social problems in the future,” says Shoaib.

The last component is, ‘Digital making’, where the students create digital artefacts instead of just consuming technology. This can be in the form of an app, website game, or animation.

The kids work on their ideas and showcase their innovations in ‘Maker’s Factory’, an annual platform that celebrates the projects they work on.

A brilliant example of a solution developed by some students deals with weather monitoring and its parameters such as humidity, temperature, rainfall, and wind speed. The students connected different sensors with their computers, and the data they collected is being used by the Indian Meteorological Society in Pune!

Shoaib believes that this also helps the kids in understanding their local climates better, thus making them climate-conscious.

This is reflective of how the kids are learning about computers and coming up with viable solutions applicable in the real world. It is when you speak to the teachers that one learns how much the kids have learnt.

Take Swaranjali Bhise, a teacher at the Epiphany School. It’s the same school where the students came up with the solution to curb two-wheeler road accidents. The school is located near slums like Bhavani Peth, Kashewadi and Ghorpade Peth in Pune.

The school has TFI fellows and thus, could connect with the NGO in June 2018. Pi Jam has installed about nine Raspberry Pi systems and helped train about 300+ kids.

“I love the fact that students are learning new things, way beyond the basics, which has gotten them really excited. They are so inquisitive, and identify problems, as well as provide effective solutions. The curriculum has also improved classroom interactions. They have also trained us, teachers, to implement the curriculum and continue to meet us every month to discuss challenges while helping us solve them,” says the 42-year-old.

Overcoming challenges for a brighter future

Running an NGO that works with over 15,000 kids is obviously not a piece of cake. But, Shoaib says that the response of the students, teachers, and even parents has been very positive. This has kept them motivated and upheld the belief that their work is making a difference.

The challenge, however, is related to compliances and regulations.

“As an NGO, our goal is to provide world-class computing education to kids studying in government-run and under-resourced schools for free. So, to really scale our initiative, we need to have sustainable revenue flows. But, the process of getting clearances and all the paperwork related to donations takes a lot of time. There have been instances where interested donors haven’t been able to contribute because of these complicated processes,” he explains.

But, through award grants and by carrying out projects in collaboration with other grassroots foundations, they have been able to manage their operations effectively.

The enthusiastic founder of the NGO also has a few plans.

He shares that they now want to introduce AI and ML (Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning) as a part of their curriculum. But, he wants to ensure that these concepts are taught in a more relevant context.

“We now hope to scale our programme in more schools through collaboration with the government. I want kids to realise that these skills are not just for securing a job but to understand the world’s ever-increasing problems and how they can come up with solutions. Our hope is that kids embrace their full potential to become the problem-solvers that the future needs,” says Shoaib, signing off.

- Viman Nagar, Pune, Maharashtra

- contact@thepijam.org

- 096546 30173

- http://thepijam.org/

Add new comment